Back home once more

How the First World War brought my great-grandfather John Harrington back to East London, the place where he was given up on as a young boy.

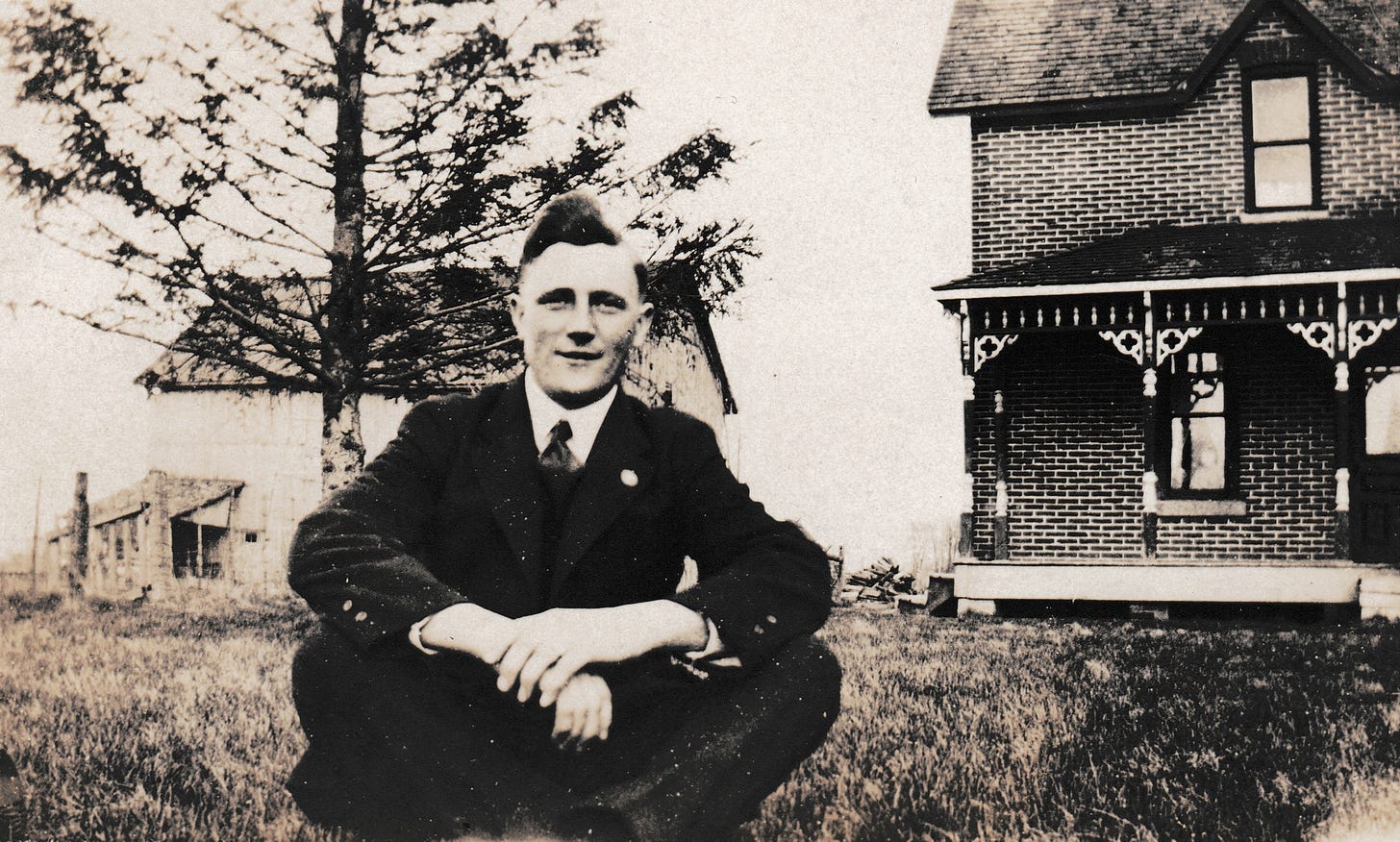

Pictured above is my dear great-grandfather, John Harrington (1894-1978). A kind-hearted man, he dedicated his life to service—to his family, raising three children through the Great Depression; to his community, working nearly 40 years in the local police force; and to his country, serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force on the front lines in Europe during the First World War.

These three pillars—family, community, and country—were things John never had as a child. Abandoned by his family, removed from his community, and neglected by his country, he faced unimaginable hardships before the age of eight. Yet, against all odds, he built these pillars himself.

John left East London alone at only eight years old, returning only once—as a soldier who would soon serve on the front lines in France, donning the uniform of the country that had given him the opportunity to create a life that once existed only in his dreams.

Born “John Wright” on July 2nd, 1894, in Upper Clapton, East London, life was harsh from the start. His father, also named John Wright, was known for being less than law-abiding and had a fondness for drink that often controlled him more than he controlled it. The elder John Wright, whose roots traced back to the farmlands of Horndon-on-the-Hill, Essex, worked as a baker and general laborer, trying to make ends meet in the industrial sprawl of East London.

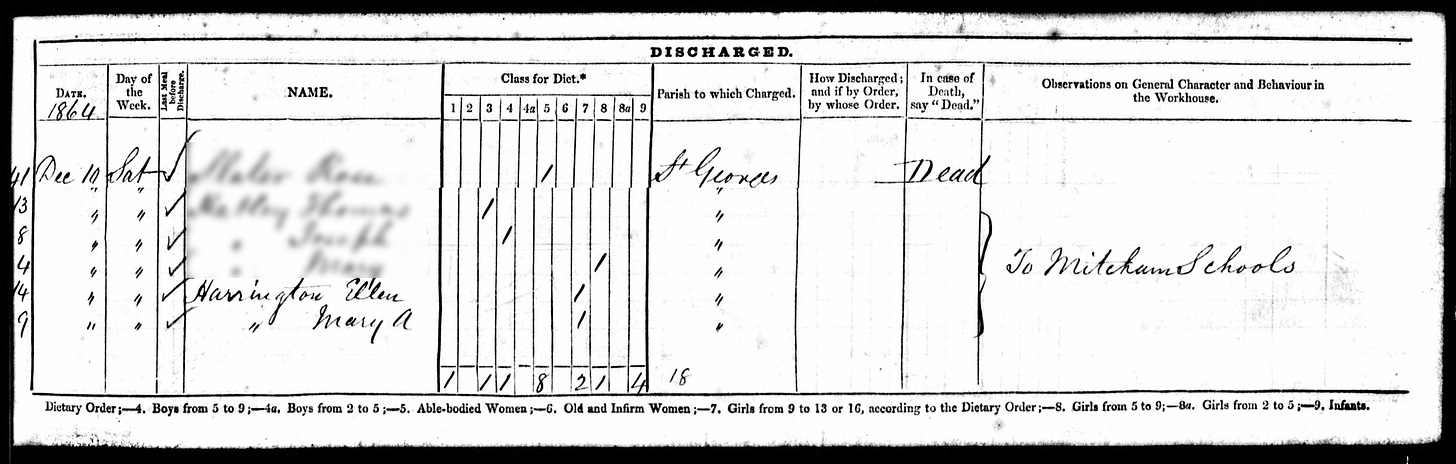

John’s mother, Mary Ann Harrington, endured her own childhood hardships. The daughter of Irish immigrants from the Beara Peninsula in West Cork, she lost both parents to disease at a young age, forcing her and her sister Ellen to endure life at the Mint Street Workhouse in Southwark and later the St. George’s Workhouse School in Mitcham, Surrey. The Mint Street Workhouse, believed to have inspired Dickens’s Oliver Twist, was notoriously grim—an unimaginably tragic place for a young girl.

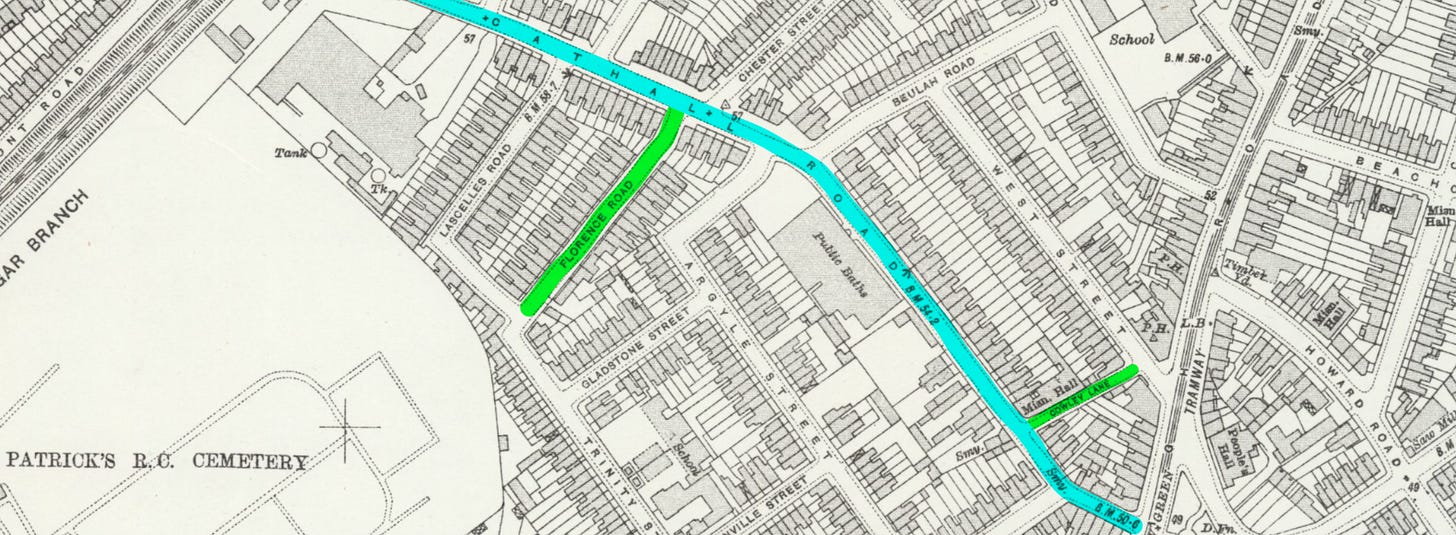

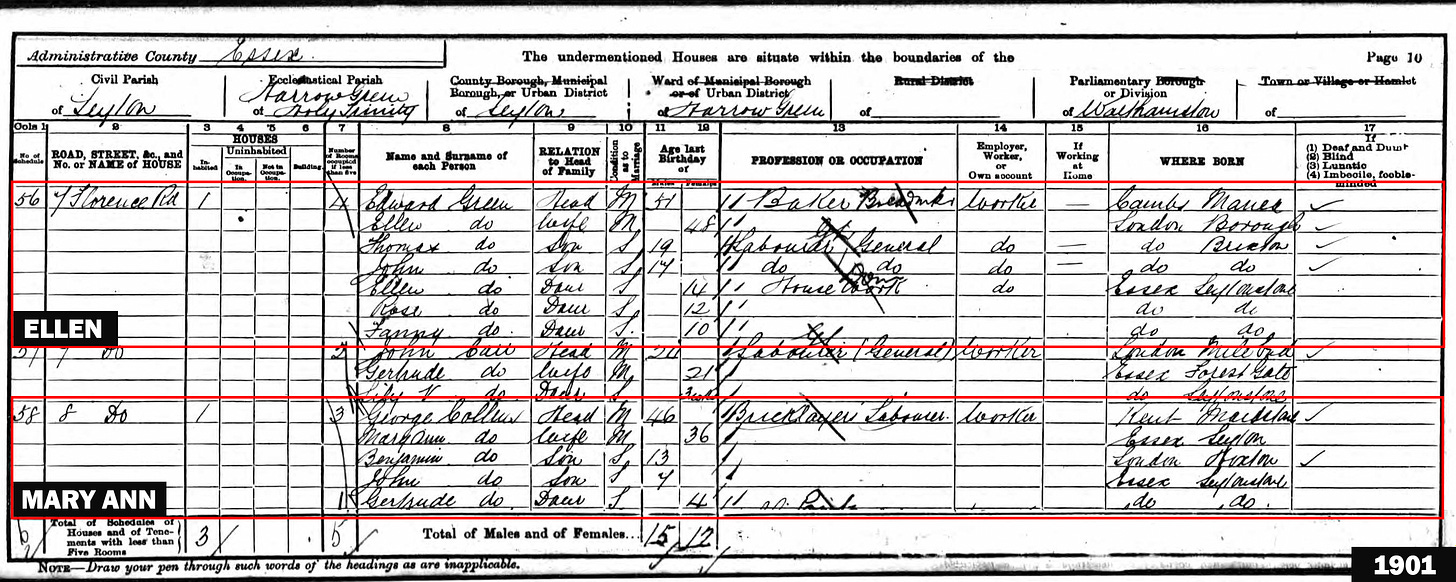

Raised in the British industrial school system, Mary Ann was released at 14 and struggled to find her place in the workforce. She moved around London, working odd jobs until around 1890, when she found herself living next to her sister Ellen on Florence Road in Leytonstone. It was there that she met John Wright, and they began a relationship.

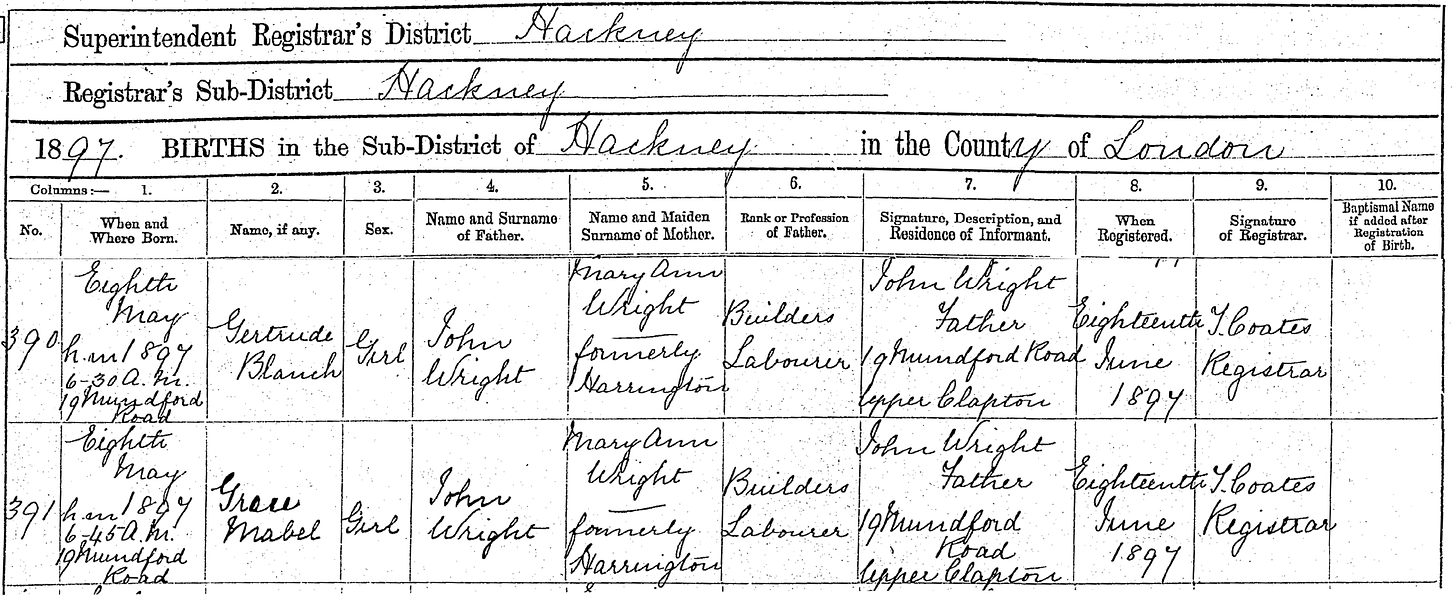

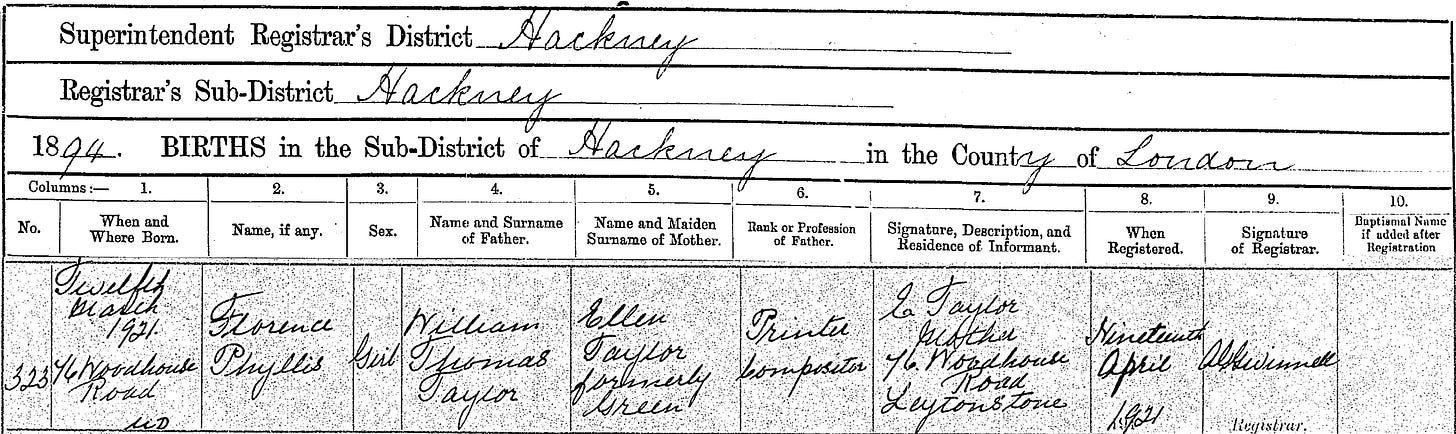

Though they never married legally, John Wright and Mary Ann Harrington had four children: Elizabeth, born July 10th, 1891; John, my great-grandfather, born July 2nd, 1894; and twins Grace and Gertrude, born May 8th, 1897. Both Elizabeth and Grace died as infants, leaving only John and Gertrude in their parents' care.

Mary Ann’s sister Ellen had more stability in her adulthood. She married William Edward Green, a journeyman baker, and together they had six children: William (b. 1877), Thomas (b. 1883), John (b. 1884), Ellen “Nellie” (b. 1887), Rosa Emma “Rose” (b. 1888), and Fanny (b. 1891).

By 1900, John Wright abandoned his young family, then living at 19 Mundford Road, Upper Clapton, leaving Mary Ann with limited means to care for her family. Alone with two young children, Mary Ann, John, and Gertrude returned to Florence Road, where Ellen and her family still resided.

It was likely during this time that Mary Ann met George Bradd (1856-1924), who had moved to 3 Cowley Terrace in Leytonstone after his wife Sarah’s death in 1898. George and Mary Ann soon lived together at 8 Florence Road, along with John, Gertrude, and Benjamin, George’s son from his late wife.

Curiously, the 1901 Census lists George, Mary Ann, and the children under the surname “Collins,” suggesting that they might have been trying to live under an assumed name for reasons unknown.

Tragedy struck for the Harrington family on July 15th, 1901, when Ellen Harrington passed away from bronchitis, leaving Mary Ann without her closest support. With the sudden loss of her sister, Mary Ann’s struggle to support her children became even more severe.

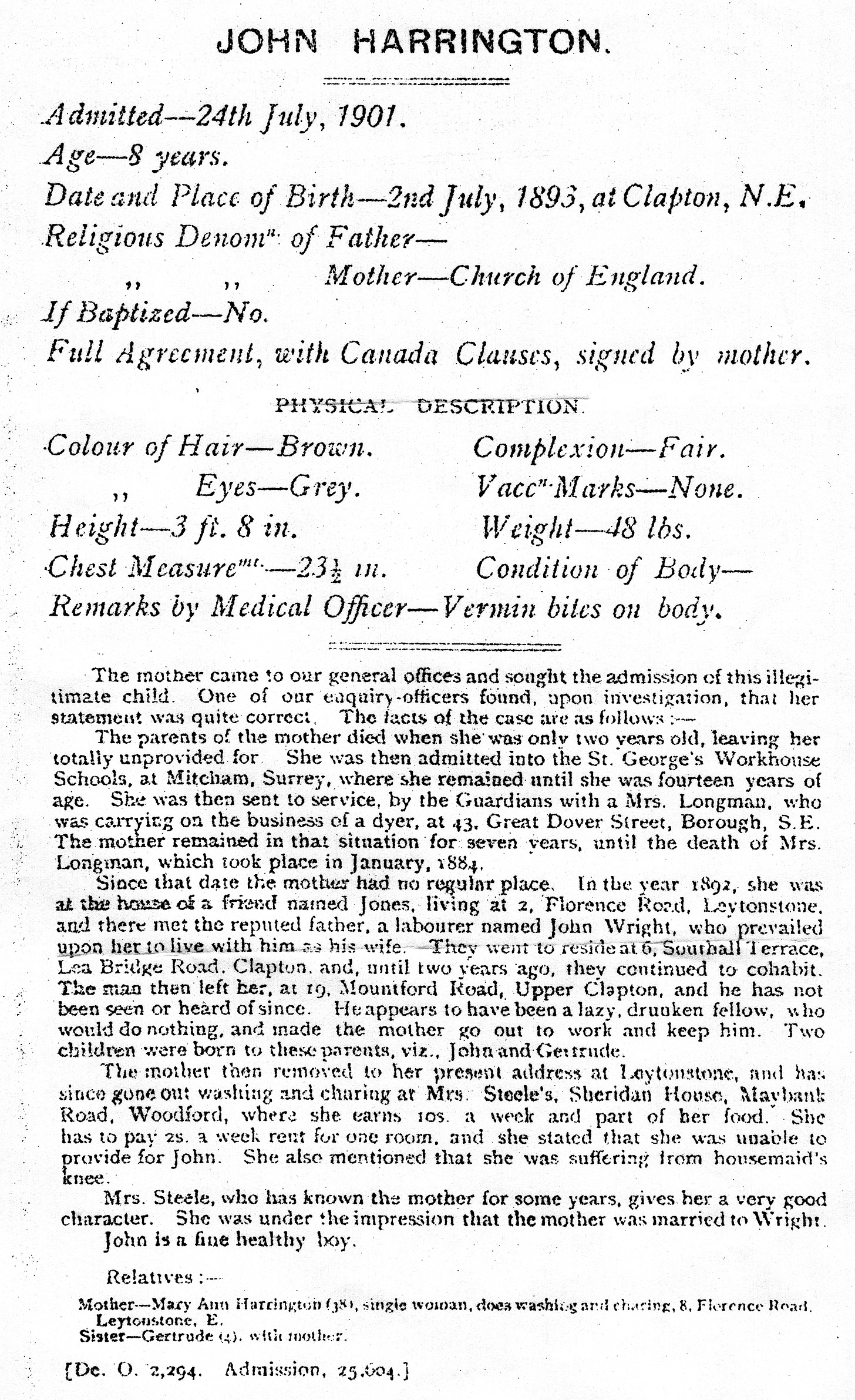

Just nine days after Ellen’s death, Mary Ann made the heartbreaking decision to bring John to Dr. Barnardo’s Homes, an East London institution for orphans and destitute children. Barnardo’s agents would canvass poor neighbourhoods, promising mothers that their children might return one day and telling children fantastical stories of life in Canada.

Admitted under the name John Harrington, for the next 14 months, John lived at The Children’s Fold, a Barnardo’s home in Bow, East London. At the time of his admission, his mother Mary Ann signed the Canada Clause, which allowed Barnardo’s to emigrate John to the British colonies as an indentured servant. There, he would work in exchange for food, lodging, and a chance at a better life.

At the age of eight, John sailed to Canada aboard the Colonian, departing Liverpool on September 25th, 1902. He was one of 30,000 Barnardo’s children who left their homes for Canada to work on farms and homesteads. In exchange these young children would receive a place to live with the family, who became the child’s employer until at least the age of 14.

Since it was Barnardo’s who had given John’s name to the Canadian immigration officials, once landing in Canada he would have become both a Canadian citizen and legally named John Harrington, per his immigration record.

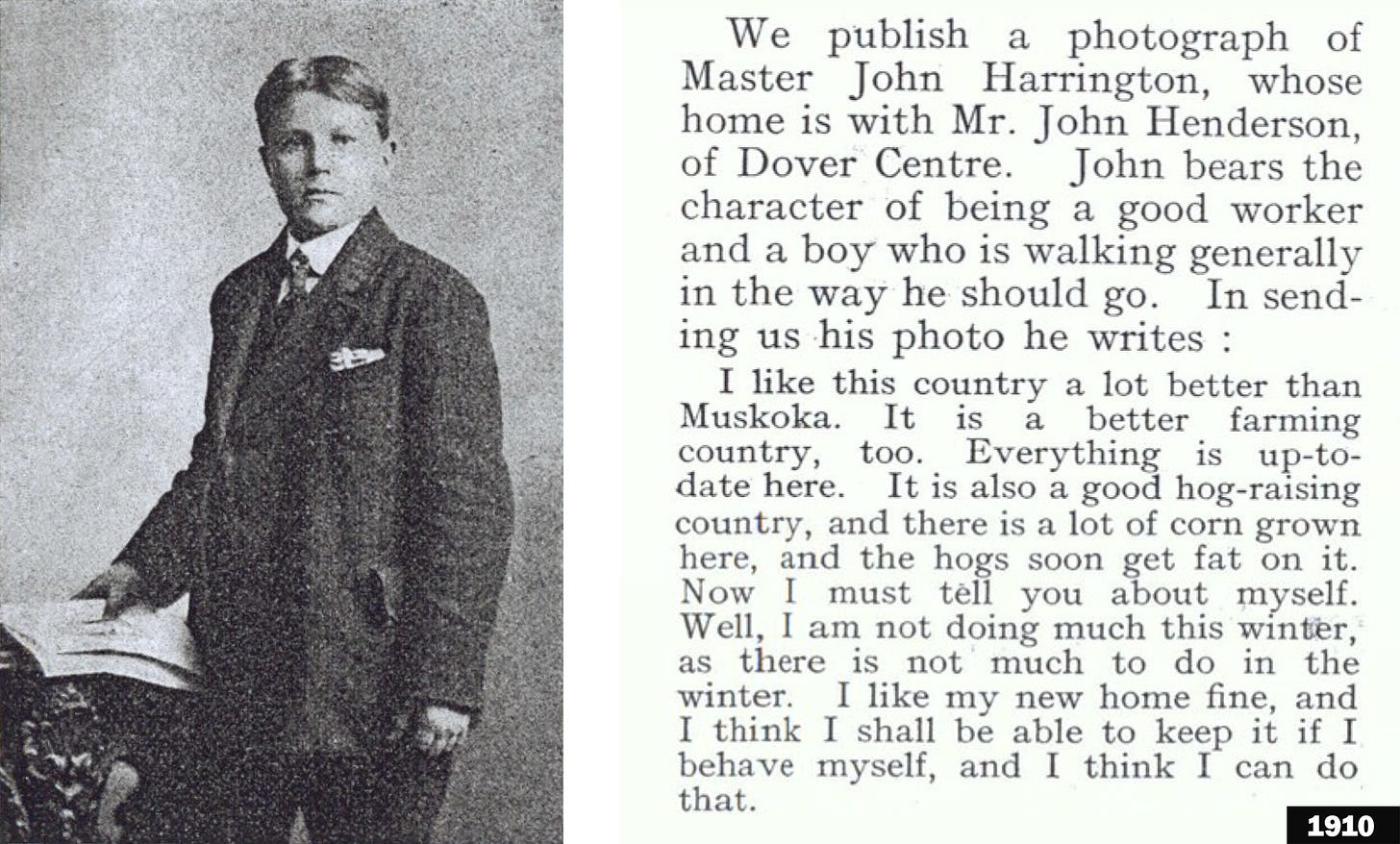

In the autumn of 1902, John was placed with the Mason family in Port Sydney, Ontario, part of the rural Muskoka region about 200 kilometers north of Toronto. There, he worked on the farm and attended school. His contract with the Mason family ended in 1909 when he was 15, and he was moved to the Henderson family in Dover Centre, near Chatham, Ontario. John and the Henderson’s had a meaningful relationship and they remained in contact throughout his life.

Dr. Barnardo’s described itself as “the largest family in the world” and published Ups and Downs, a magazine distributed to Home Children across the globe. In the May 1910 issue, John’s photograph and letter were published, detailing his recent move from Muskoka to Dover Centre. It’s quite sweet imagining one of the Henderson’s assisting John with writing this letter.

In the fall of 1917, John was conscripted into the Canadian Army, enlisting in London, Ontario on March 4th, 1918. He listed his mother, “Mary Harrington,” as his next of kin with the simple address, “London, England.” One month later, he returned to England, training at Seaford Camp in Sussex before being deployed to the front lines in France by early summer. He fought in Canada’s Hundred Days campaign, a decisive offensive aimed at ending the war within 100 days.

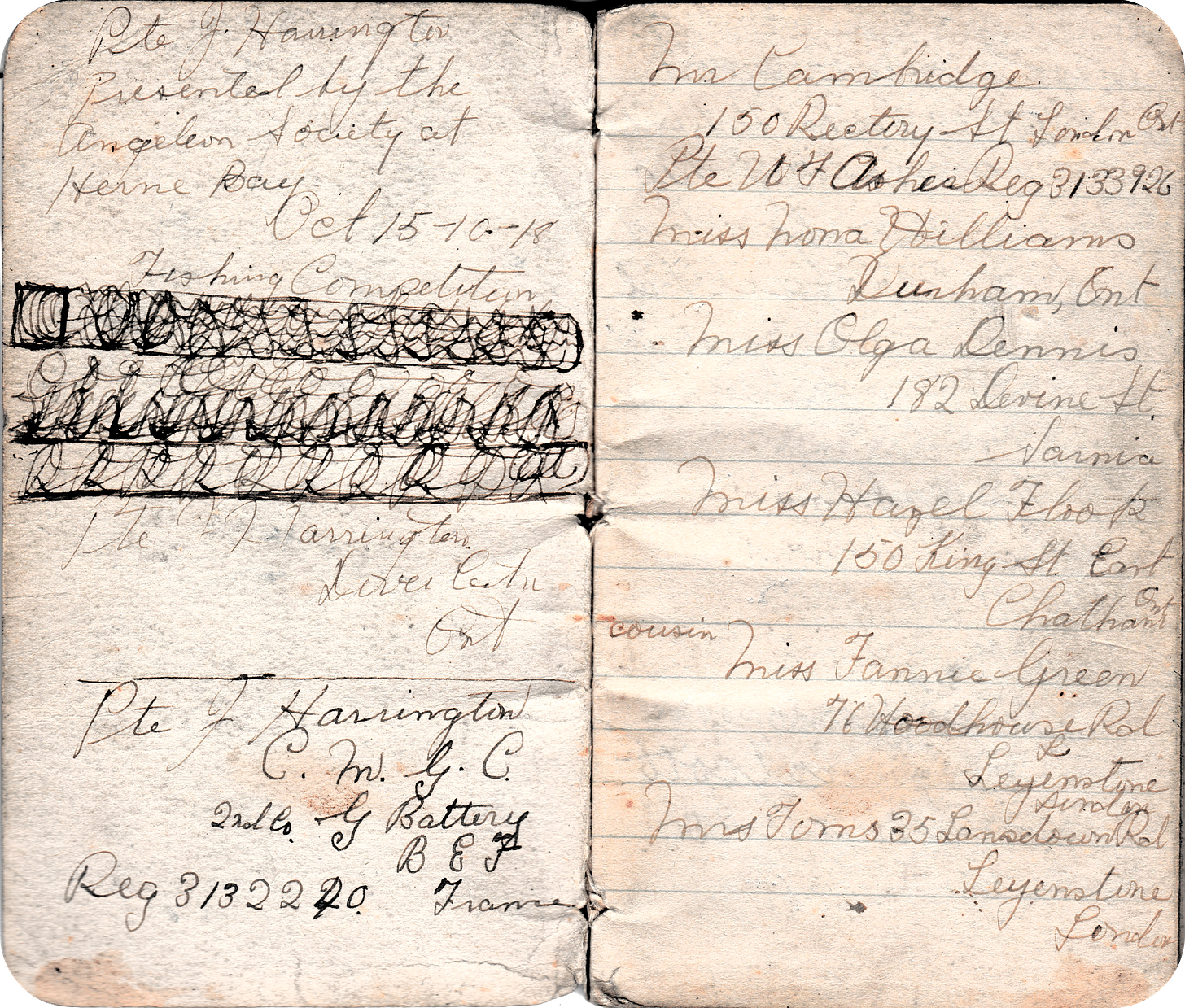

John was wounded on September 29th, 1918, during the Battle of Canal du Nord near Cambrai, struck by shrapnel in his head and back. He was transported to Herne Bay Railway Men’s Convalescent Home in Kent, where he remained for the rest of the war, which was not far away at this time.

While recovering, John sent letters and photographs to his sister Gertrude, who was training as a nurse at Queen’s District Training Home in Leytonstone. During his recovery, the local Angling Society held a fishing derby at Herne Bay Pier for the wounded soldiers. John, an avid fisherman, participated, and although a porpoise scared the fish away, it was a welcome distraction from the war.

Each soldier in the derby received a small black notebook as a prize. John used his to record names and addresses. On the first page of entries he recorded were his cousins Fanny Green and Rose Green (now Toms), who lived at 76 Woodhouse Road and 35 Lansdowne Road, Leytonstone, respectively. He reconnected with them—his childhood companions—more than 15 years after leaving.

John’s cousins, who had grown up with him on Florence Road, had weathered the war as well. William Green, who served with the 4th Battalion Essex Regiment, lived with his sister Nellie and their brother at 76 Woodhouse Road. Thomas Green, another veteran, stayed with Rose at Lansdowne Road.

In 2022 I connected with descendants of Rose Toms, who I matched with on AncestryDNA, and shared my great-grandfather’s story with them. They found it very touching and we are now in regular contact, allowing this connection to live on in the 21st century.

John returned to Canada in late 1919, having spent time in Edinburgh and London, where he marvelled at sights like Tower Bridge. In a postcard dated October 20th, 1919, he wrote to a friend about how “magnificent” the city appeared to him—a place he now viewed with a sense of belonging.

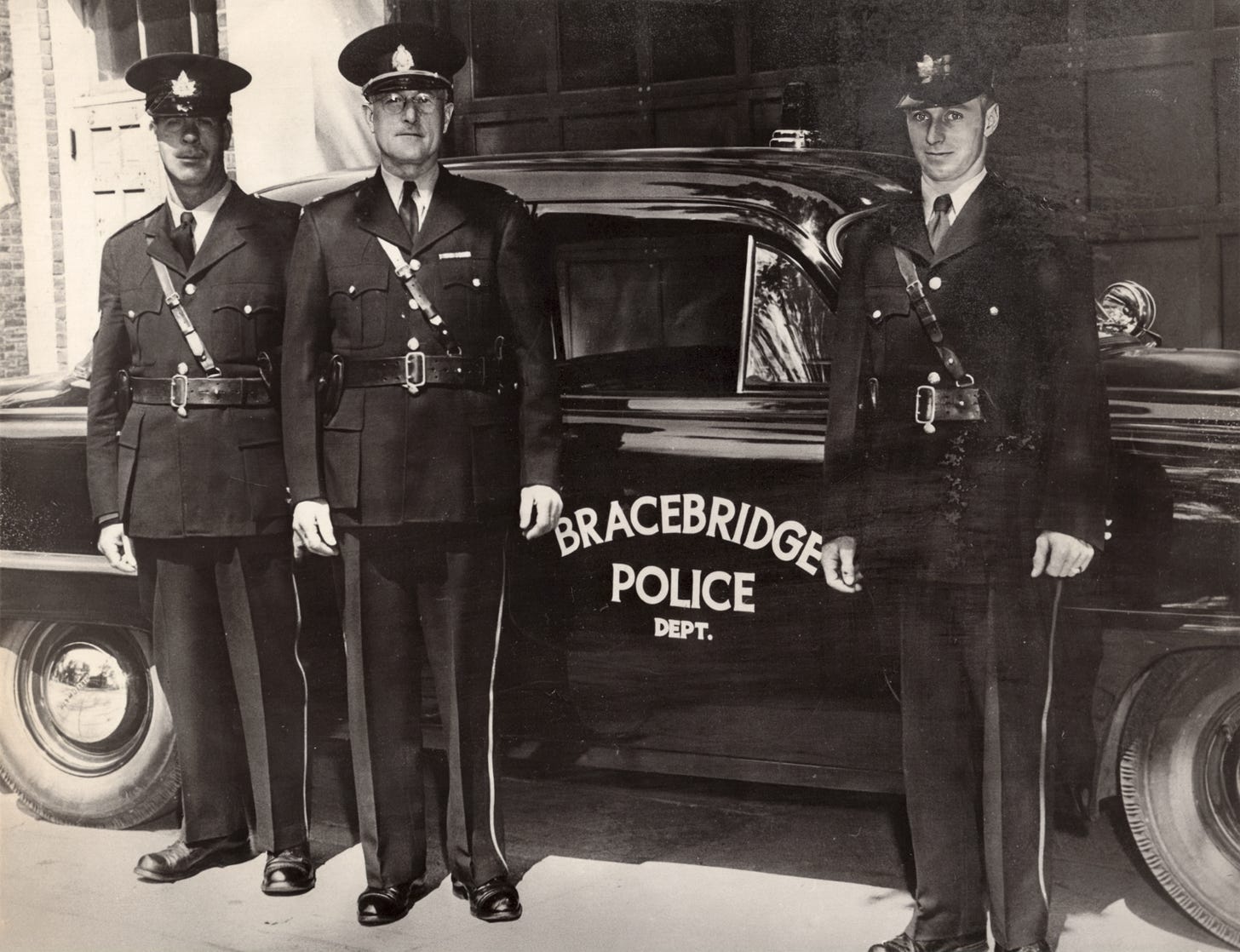

Settling back in Canada, John explored civil service roles as a postman and fireman before finding his calling in 1927 as a constable with the Chatham Police Force. He became a dragnet-style plain-clothes detective in 1940 and, in 1948, accepted a position as Chief of Police in Bracebridge, Ontario—my hometown—serving until his retirement in 1965.

In 1953, John Harrington received a medal from Queen Elizabeth II for his exceptional contributions to the community of Bracebridge. The accompanying placard read, "By command of Her Majesty the Queen, the accompanying medal is awarded to J. Harrington Esquire." It was a moment of immense pride for someone the kingdom had all but forgotten about.

My great-grandfather, John Harrington, passed away in June 1978 at the age of 83. His final years were spent at The Pines, a long-term care home in Bracebridge. Even during those years, he remained committed to service, dedicating countless hours to organizing various committees and social events for the residents. His unwavering dedication to helping others defines his legacy and continues to inspire me every day.

Happy Remembrance Day, great-grandpa! Thank you for your service and then some.

🌹🌻🌸💐💚💛💜❤️🌼😍🥰

Wonderful article about your great-grandfather. A very challenging beginning, but clearly well-loved young man.